[First published in The King’s Tribune, 2013]

Recent prognostications on whether there is a housing bubble going on are only looking at part of the complicated picture of where Australians call home. For the 30% of Australians who rent, finding secure and affordable housing is getting harder. And for those on the lowest incomes, it is damn near impossible. Yet, once upon a time, an Australian government enquiry found that citizens had a right to a home.

Housing – its tax status, regulation, availability and cost – is an inherently political issue. Yet, it didn’t feature in the recent election campaign nor is it in on the new Federal Government’s agenda.

Newspapers use the last of their incoming advertising dollars to report on increasing prices and intergenerational bickering over housing costs. In the meantime, those who rent are finding this a more and more difficult proposition, in both the public and private systems.

The aged pension is structured around an assumption that people will own their own homes at retirement. However, for those without a home, the private rental market is increasingly precarious. People with disabilities are often are pushed further and further from services and employment in a quest for affordable housing. Community services cite the cost of housing, particularly in private rental, as the key concern for people on low or moderate incomes.

Rental vacancies are low, even in high-priced areas, with many on average wages unable to afford to rent anywhere near their jobs.

At the same time, public and social housing has contracted substantially, now only available for the most vulnerable and disadvantaged people. Housing departments are increasingly using regional motels to fill the gap in crisis accommodation.

But has it always been like this? What have governments done in the past?

Government interest in housing was at its peak after the Second World War. And extensive enquiry led to direct investment in building large amounts of new homes, aimed at workers. The Commonwealth Housing Commission took on the edict that:

“We consider that a dwelling of good standard and equipment is not only the need but the right of every citizen – whether the dwelling is to be rented or purchased, no tenant or purchaser should be exploited for excessive profit.”

[Source: The Brown Couch.]

By 1966, nearly 1 in 5 Australians were living in public housing. (For some more fascinating history of all this, have a read here, here and here.)

Now, the idea of government providing housing for low income workers seems far fetched. Gone are the days of the government owned prefabrication factory, that turned out up to four houses a day. Instead, the Commonwealth spends over $3 billion on a meagre rental voucher for those on the lowest incomes in private rental. State and territory governments are redeveloping old estates and selling off the more profitable bits, but not adding to the existing public housing stock.

So why does the matter? Surely the market is the best way to sort this out? High housing costs mean that more will be built, doesn’t it? Well, no. Fewer new dwellings are being built that the amount needed, pushing up prices for everyone – or at least everyone who can afford to buy.

But just looking at building starts doesn’t answer the housing question for those who will never be able to afford high costs. If an older woman, after raising her kids and being part of her neighbourhood for decades can no longer afford to stay, the market dictates that she should be forced to move far away, no matter the consequences or the cost to her. And what about people working in low wage jobs, like childcare or cleaning? Where do they live? Where are their rights as citizens to not be “exploited for excessive profit”?

One of the problems about the rhetoric of the free market in housing is that it isn’t true. Housing is treated very differently to other asset classes, with tax breaks for the ‘family home’ and ludicrous subsidies for landlords. The cost of negative gearing alone is over $13 billion, with no sign that it has done anything to reduce the cost of housing, instead doing the opposite.

Now there is also a rush of self-managed superannuation funds into the housing domain. Again, favourable tax treatment distorts the market with incentives at the top of the income pile, rather than the bottom.

The previous Federal Government at least recognised this as a challenge. In 2008, the National Rental Affordability Scheme was set up to encourage investment into the other end of the market. Those building places to rent at 20% below the market rent receive an subsidy – last year’s was just over $10,000.

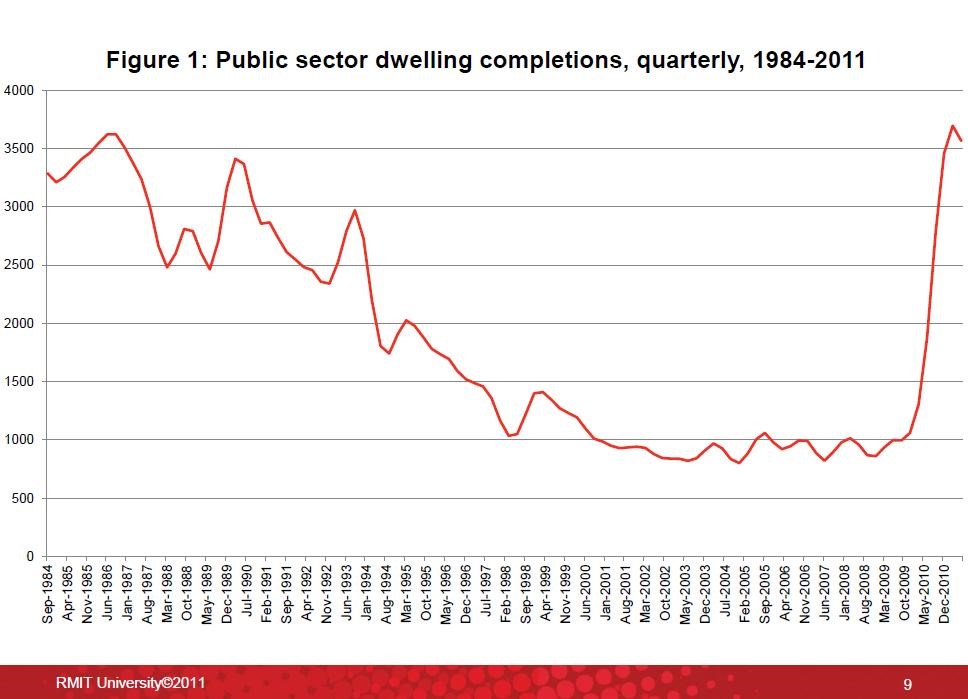

The impact of that program is clear.

[Source: Hayward, AHURI presentation.]

But again, this is just tinkering on the edges. There are over 170,000 people waiting for a public housing place, and an estimated 493,000 more affordable rental places needed overall. Australians for Affordable Housing has some interesting ideas on the scale of the challenge.

Rental security is another factor off the policy radar. Australia doesn’t offer long-term leases in the same way many European countries do, leading to tenants being forced to move. Renting has, policy-wise, been seen as a temporary stop on the road to home ownership. But this is no longer the case, with many people now renting long-term. A study from the Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute in 2012 pointed out that:

“It was assumed that renters would quickly move into home ownership or, if not, would obtain these benefits from social housing. These assumptions have been undermined by two trends. First, housing affordability problems mean that households on low to moderate incomes find it difficult to purchase a home, and longer term renting is becoming more common. Second, the social rental sector has insufficient accommodation to house many of those on low incomes.”

In Germany, for example, up to 60% of people rent, with longer leases allowing for tenants to do minor renovations and establish themselves in neighbourhoods, without the constant uncertainty that Australian tenants have. Other countries have far greater investment in social housing, understanding that housing is not just about house prices.

Australian housing policy once acknowledged that housing was a

fundamental right for its citizens. Not so they could make money, but so they

could be safe and secure in their own home. Our current political and policy

settings say that a home is now only for those who can afford it; for the rest,

it is but a dream.